'The Empire Writes Back' would have been a fitting alternative title for this essay collection. (Achebe doesn't fail to pay a tribute to Salman Rushdie's essay of the same name published in 1982).

Because that is what the running theme here is - a reclamation of a land and a culture that was wrested away with brutal force and made a part of an 'Empire' which still insists on viewing that period as one of glory and not characterized by the worst kind of human rights violation ever. And a heraldin 'The Empire Writes Back' would have been a fitting alternative title for this essay collection. (Achebe doesn't fail to pay a tribute to Salman Rushdie's essay of the same name published in 1982). Because that is what the running theme here is - a reclamation of a land and a culture that was wrested away with brutal force and made a part of an 'Empire' which still insists on viewing that period as one of glory and not characterized by the worst kind of human rights violation ever. And a heralding of the arrival of the African voice in the world literary scene.

Achebe is slowly turning into my personal literary hero. His wry humor, elegant prose, mildly sardonic tone and passion for social justice exude a righteousness that's hard not to defer to. His writings continue to make me question certain pet notions and ideas that are so deeply ingrained in each one of us that they seem like indisputable facts and consequently evade further introspection.

My penchant for unconsciously comparing Latin American, South East Asian and African writing to the style, technique and language of the Americans and Europeans I admire and immediately pronouncing judgement on them on the basis of said parameters has to go away now, I realize. It doesn't matter if African, Asian and other writers of the Commonwealth (Dear god, why do we have that ridiculous redundant grouping still?

Is it not there for the sole purpose of reminding us that we were once colonies?) have the same degree of grammatical precision and structural integrity to their English prose as their European and American counterparts. It matters that their voices be heard and universally acknowledged and the overlooked truths, their narratives highlight, be analyzed without bias.

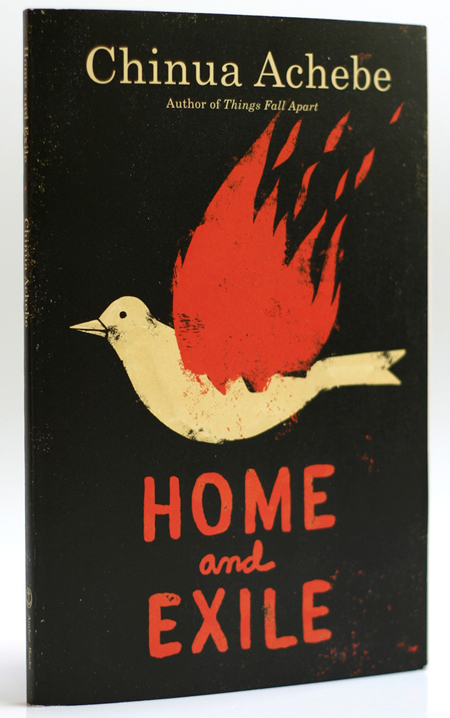

Although this collection consists of 3 essays titled 'My Home Under Imperial Fire', 'The Empire Fights Back' and 'Today, the Balance of Stories' it should be considered a single body of work or discourse intended to dispel certain flawed notions about African people who are often derogatorily referred to as 'tribes' and automatically consigned to a lesser category of humanity. Download Free Mtv Splitsvilla 4 Theme Song there. Achebe begins with his reminiscences on his early years as a young university student in Nigeria, reading literature based on Africa authored mostly by British and European scholars who, of course, liberally manufactured painfully offensive 'facts' regarding the intellectual and anatomical inferiority of his fellow brethren and propagated the theory that European acquisition of their land and sphere of existence was for the sake of their own personal benefit. This is what Achebe says about the interlinked nature of inherently racist literature of the time (he is sophisticated enough not to use the word 'racist' even once though) and the Atlantic slave trade:- 'I will merely say that a tradition does not begin and thrive, as the tradition of British writing about Africa did, unless it serves a certain need. From the moment in the 1560s when the English captain John Hawkins sailed to West Africa and 'got into his possession, partly by the sword and partly by other means, to the number of three hundred Negroes,' the European trade in slaves was destined by its very profitability to displace trade in commodities with West Africa.' Achebe directs his suppressed ire at Anglo-Irishman Joyce Cary who was regarded as one of the finest novelists of his time and his creation 'Mister Johnson' which Achebe systematically breaks down and interprets as a text strewn with viciously hateful commentary on Africans. Another renowned novelist and polymath who had considerable first hand experience of Africa, Elspeth Huxley, isn't spared either as her criticism of Amos Tutuola's 'The Palm-Wine Drinkard' as a 'folk tale full of queer, distorted poetry, the deep and dreadful fears, the cruelty, the obsession with death and spirits, the macabre humour, the grotesque imagery of the African mind' comes off as an insidious denunciation of all African literature in general.

However, one indisputable fact can be noted about Chinua Achebe dure ing those two decades of novelistic silence: He became Africa's most deservedly beloved writer. In Home and Exile (2000), a series of lectures Achebe delivered at Harvard in. I998, the writer made the following remark: Well, it is not true.

Latest Posts

- ✔ Free Download Hp Deskjet 1050 J410 Driver For Windows 7

- ✔ Dragon Ball Z Sparking Meteor Ps2 Iso Zone

- ✔ Denki Groove Yellow Rari

- ✔ The Auteurs New Wave Rar

- ✔ Download Film Anime Sacred Seven Sub Indo

- ✔ Rejjie Snow Rejovich Rarest

- ✔ Dns Server Configuration In Linux 6 Step By Step Pdf To Word

- ✔ Steam Serial Keys Generator Steam

- ✔ Linguatec Personal Translator 2008 Propel

- ✔ Hfss Linux Cracker

- ✔ Pro Light 1000 Software Companies

- ✔ Magix Music Maker 2014 Soundpools Download Free

- ✔ Download Game Pes 2012 Untuk Android Samsung Galaxy Y

- ✔ Moscow The Power Of Submission Download Music

- ✔ Cs Portable Map Editor Download

- ✔ Ricettario Bimby Ebook

- ✔ A Modern Method For Guitar Volume 1 Pdf

- ✔ Mario Kart Wii Iso Rar Downloads

- ✔ Afrojack Steve Aoki No Beef Download 320kbps